World Events Are Raising Questions About Adapting the Structures of Supply Chains – Learnings to Answer Them

We’re starting to hear more about it. Company leaders are asking, “What do we need to do to make sure this doesn’t happen again?” Lost sales, lost opportunities, business closures, re-opens, higher debt loads, high inventory, no inventory, confusing/conflicting government rules, safety protocols, work-at-home, restructuring, layoffs, hiring, supplier and customer issues, internal issues, what is temporary vs. what is the new norm. Obviously, some of the fall-out from the pandemic is not impactable, but some of it is and how teams address it certainly is.

It’s more than the pandemic too as many countries deal with other challenges in parallel. In the USA we are also dealing with a vulnerable economy, 11% unemployment, on-going international political tension, racial tension, and an upcoming contentious presidential election that will once again force most voters to pick their poison. All of this means a steady increase in business complexity for the foreseeable future. Some will say, “we’ve got it covered”, but most will admit at least to themselves, that they have soft spots.

The easy questions that don’t have easy answers

Not all questions apply to everyone, but when they do apply, they’re easy to ask. In some cases they come from the top floor, head office in another country, or from peer executives that lead other functions right on your own team.

- Should we bring our manufacturing back to the US/other country? (Tax incentives are coming for US companies if the current administration gets reelected)

- Should we do more business (and leave the cash) in more tax-friendly countries? (Corporate taxes are going up a third in the US if Biden gets elected and can get his desired tax plan through congress)

- Should we seek to invest in countries where there is less political risk?

- What are our customers and suppliers doing?

- Should we seek alternative suppliers since our present partners fell short during the pandemic?

- Should we vertically integrate more or less?

- Should we write-off/down that inventory, move it through our discount channel, or hold it, slowing our manufacturing and dealing with the knock-on effects from that?

- Do we really need all this office space?

- How much is all this cleaning going to cost? How will safe operation affect cycle time and what are the resulting impacts on lead time and inventory? What is safe, anyway?

- What do we need to do to become more ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) friendly and how do we emphasize more of that?

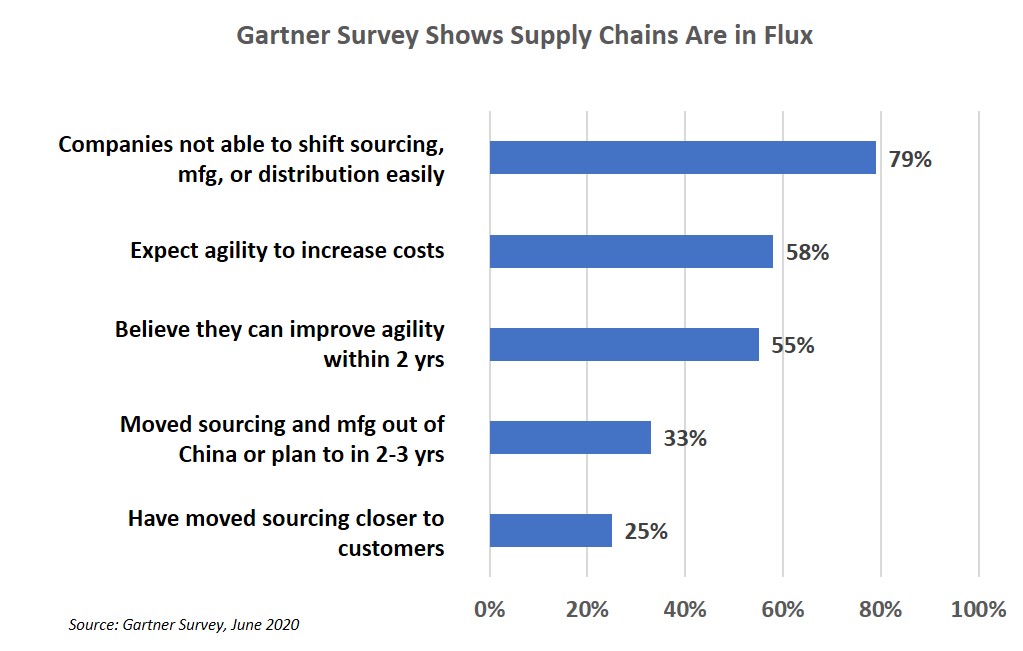

A Gartner survey shows that supply chains are in transition

A June 2020 survey of 260 global manufacturing companies from North and South America, EMEA, and APAC shows that supply chains are in flux.

What all this means for supply chains

In one simple word, it means trade-offs. Perhaps business experience and gut feel will point leaders in the right direction, but gut feel doesn’t always cut it if you answer to someone or work in a consensus driven organization, which is most of us. You need the business case.

Managing trade-offs obviously isn’t new and is the essence of supply chain. What is increasing is the degree that supply chain leaders will be called upon to justify a new course or stick with the status quo. They’ll need time, skills/people, and DATA to pull it off.

The trade-offs involve the usual suspects of revenue, cost (one-time and recurring), inventory, lead time, capex, and of course cash flow. There are lots of interactions among these variables and modeling them to optimize for a chosen variable (typically profitability or cash flow) isn’t always so easy. If you don’t have a real model, someone will likely ask/demand too much across the conflicting set and commitments will be made from ignorance.

Modeling your supply chain “Geometry”

When I say Geometry, I mean the structural configuration. These are things like manufacturing facilities, distribution network, supplier network, and related decisions about outsourcing. The poor man’s approach of Excel can perhaps get some directional thought and discussions going, but it’s hard to model all the interactions. Also, as with most Excel models, the only one who can actually understand it and use it is the one who built it, and we know where individual people dependencies usually leads. The Excel model may be okay for a quick and dirty, skinnied-down (i.e. cheaper) consulting project to explore a discussion, but it’s not a real answer.

The capability to model your supply chain is an on-going need. Without this capability, you’ll pretty-much be starting from scratch on the spreadsheet each time. An on-going modeling capability should be thought of like any other supply chain capability, like demand planning or procurement. Often it’s left out of the quiver, as it goes back to that “urgent vs. important” thing most of us and budgets struggle with.

A couple case experiences with tools for this

How did it go? In one word, mixed. While I generally support the use of real tools to produce real answers, no-one can just pick up a guitar and walk out on stage. They need both skill and a song to play. The tools are getting more cost effective and easier to use, but what hasn’t changed is the math, and the math needs DATA. Typically the gap here is having the right cost data. I can see where some work is required to get good cost data for a “to-be” situation (like moving to an outsourced manufacturer), but not being able to easily populate your baseline data into the model is a little like a home improvement project at my house. You’re trying to get one thing done, and six other things come up that need attention before the intended job can be tackled. In the meantime, the board meeting is in a month and your CEO and management team are going to field the questions the board lobs in as discussed at the beginning of this article. So easy to ask.

Manufacturing footprint changes

When software companies say you’ll have a complete model in “x weeks” (4 is a popular number), that means accurate data are available immediately to just type or import in. For most companies, you should double or even triple the time they tell you. In one case, we spent 12 weeks building a model and never could quite get the data from those plants in developing countries and we ended up going back to the quick spreadsheet model and gut feel. Twelve weeks and $$$ on model development and the rented tool wasted.

Distribution network changes

This project was better. This company had 23 warehouses in the United States, OMG! The network grew organically based on the commercial organization’s preferences that had evolved informally over time. This situation was not uncommon before supply chain organizations started to appear over the last two decades (we did some org work for them too!) and this situation still occurs in lagging org structures. We modeled a solution that showed the company needed 5 warehouses to reach all US customers within 1 day. This is typical of US distribution. We were able to “negotiate” with the commercial team a design that got them to 11 warehouses. Sometimes you don’t get it all, and this was a significant first step. The model took longer to build than was anticipated, but we built a good one. In this case, a key use of the model was also change management. “Hey, it’s a fancy tool developed by these very smart people, it must be right and better than your gut feel, right?” Right.

Build the on-going analysis capability

Both tools used in the above examples are good and visible in the marketplace today, but success was determined by data quality, not tool quality. If you want to be a supply chain, but don’t have good data or capability to do something with it, you’re either so good that you don’t need numbers, or you’re mostly in the executional space without knowledge of your best supply chain strategy.

Models as described above should be built and refined over time, not in some panic to meet an aggressive project timeline or to produce an answer for a meeting. While more questions are coming during these times, even in “normal” times, there’s complexity, confusion, competing agendas, and change anyway. Supply chain teams need to be able to adapt to business conditions on an on-going basis. Build this capability to drive the best decisions or the loudest voice in the room will prevail.

Sales & Operations Planning maturity likes to talk a lot about scenario modeling, but this goes beyond changing parameters for an existing supply chain geometry. I’m talking about major supply chain strategy and structural changes that aren’t drag and drop.

Obviously implementation of any supply chain structural change is a major project, but I’ll leave that alone for now. I also wanted to talk about the framework for managing decisions around supply chain changes as well (Sales & Operations Planning), but seems that should be a separate article too. Will be back on that one in the future.

What are others doing now?

See the real-time results of our on-going survey on what supply chain changes others are considering and implementing to deal with world events.