Considerations When Rationalizing Your Product Portfolio

While product rationalization is an integral component of product life cycle management, it is often neglected because it involves change and can cause ripples throughout the organization. After all the time and money that companies put into launching, building, and selling products, it’s understandable that they are hesitant to let them go. On the other hand, if products are not rationalized, their numbers continue to increase and they add complexity, potential confusion, and certainly increased support costs. The research shows that the vast majority of products are not successful. Most agree that product rationalization is a good idea, but when it comes down to it, organizations often find reasons not to pull the trigger. Here are a few things that can come up when going through the process.

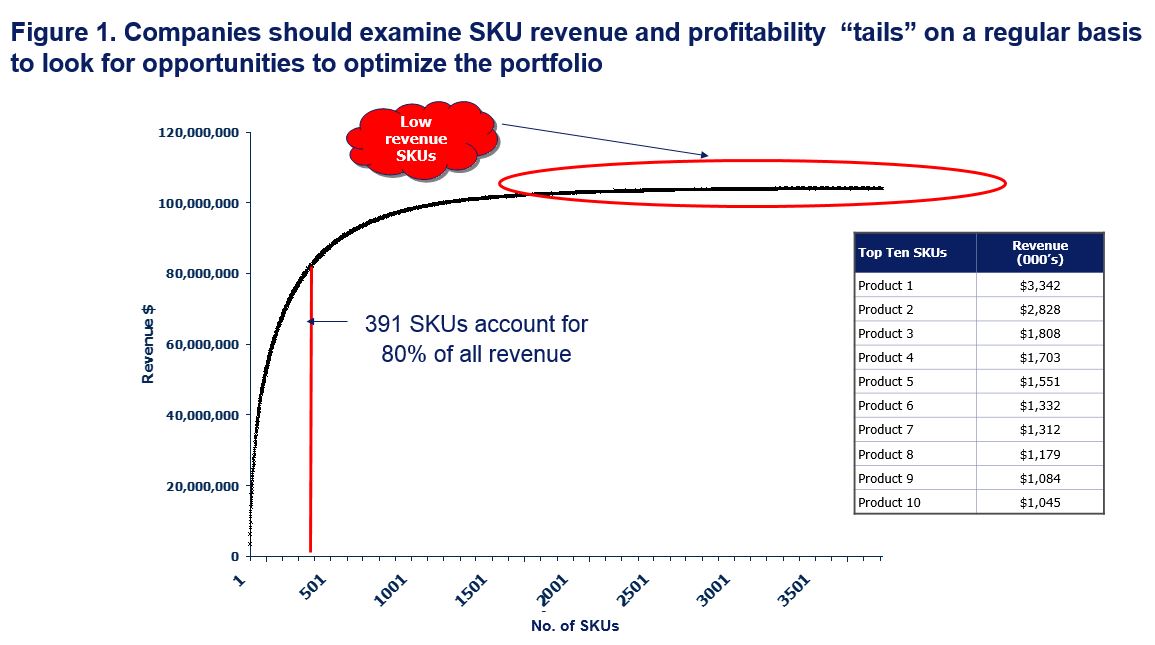

Start With an Analysis Using the 80/20 Rule – In every analysis I’ve done on revenue and profitability by product, you find that the bulk of the revenue and profit comes from a small fraction of the products. (The same thing holds true for customers too.) In fact, I’ve found it’s usually more extreme than 80/20. A graph of cumulative revenue (and another for profit contribution) by product will produce a long tail demonstrating the minor financial value of the majority of products. This is a good rational place to start, however, several other factors enter into the process when actually removing the products and what typically becomes a business decision. Here’s a few to consider:

You should create a similar chart for profitability too.

Portfolio Effect – The effect of the removal (or addition) of the one, needs to be considered on the many. While cannibalization effects are typically considered during the product introduction process, this should be reexamined during the rationalization process. Will sales go to other products or will they just be lost?

Lost Sales – While these sales are out on the tail of curve as explained above, the potential for lost sales of any kind is usually difficult to explain to sales leaders. Although overall, the rationalization may be a good idea by virtue of reducing complexity in the supply chain, redundancy in the portfolio, and support costs, these costs can sometimes be difficult to quantify. Some percent of sales that will not be transferred to other products should also be estimated. This loss needs to be made up for and exceeded by new products coming into the portfolio or growth in existing products, so the company still stays on an overall growth path.

Production Overhead Costs – When products come out of the portfolio, fixed costs usually stay the same and now must be spread across the remaining products thereby increasing unit cost and putting a damper on the day for manufacturing leaders, not to mention on their incentives. It’s important that the production volume be transferred to new or more profitable products, if demand for these exists.

Customer Migration – The prior points have emphasized the need to maintain sales and volume. To ensure this, migration plans must be made with customers and the phase out planned through Sales & Operations Planning.

Strategic Considerations – Is the product sold to customers that also buy other, more profitable products, and do these customers want one stop shopping? If so, it may be necessary to retain the laggards at least for a while to retain the business of the others.

While it’s especially important in high SKU industries such as consumer products, all companies need to have a defined process to maintain their product portfolios. Software tools are also available to help with this process and analysis. In the end, it comes down to a business decision using the best quantification of the items discussed above.

Does your S&OP process have a Portfolio Review? Should it?

See what others are doing in their Portfolio Review meetings